Lecture - Dr. Marcus Bennett

Department of Political Psychology

April, 2025

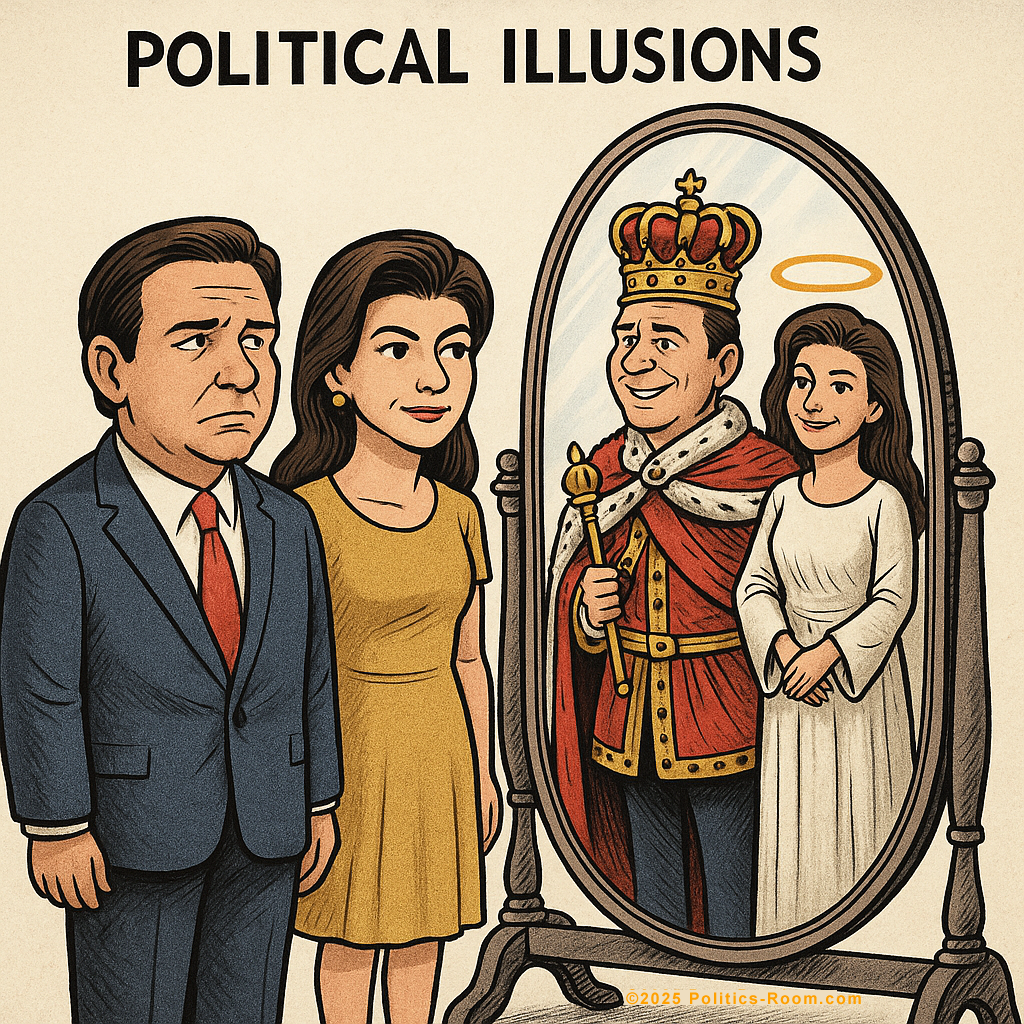

Welcome to today's lecture on Political Illusions. We'll be examining the psychological mechanisms that enable political figures to justify ethically questionable actions while maintaining positive self-perception and public support. Using contemporary case studies, we'll explore how moral conviction, family dynamics, institutional power, and rhetorical strategies create environments where political illusions flourish and accountability diminishes.

As you'll see, these psychological dynamics transcend partisan lines and appear across the political spectrum, though they manifest in different ways depending on ideological frameworks and institutional contexts.

When political figures engage in ethically ambiguous conduct, they rarely perceive themselves as wrongdoers. Instead, complex psychological mechanisms allow them to maintain a positive self-image while taking actions that outside observers might view as corrupt or improper.

Political illusions—the gap between how political actors perceive their own behavior versus how it appears to objective observers—are not simply matters of individual psychology. They emerge from intricate interactions between:

What's particularly fascinating is how these mechanisms allow individuals who genuinely believe in their own integrity to engage in actions that, to outside observers, appear clearly improper.

Student 1: Professor Bennett, I've been following the news about the Hope Florida Foundation controversy with Casey DeSantis. It seems like the DeSantis administration genuinely doesn't see any problem with redirecting that $10 million from the Medicaid settlement to fight against marijuana legalization. How does that relate to what you're describing as "political illusions"?

That's an excellent example to discuss, and quite timely. What we're seeing in that case illustrates several key psychological mechanisms we'll cover today.

The Hope Florida situation demonstrates what psychologists call "moral licensing" and "definitional shifting" in action. When a politician with strong moral convictions about an issue (in this case, opposition to recreational marijuana) believes they're acting in the public's best interest, they may rationalize procedural shortcuts or funding redirections as justified by the greater good they're pursuing.

We also see clear examples of how family dynamics intersect with political power, as the charity founded by the First Lady became intertwined with state governance in ways that blurred standard accountability boundaries.

Let's explore these mechanisms more systematically, and we'll return to this case study as we progress through the lecture.

Moral licensing occurs when individuals use their positive self-concept or previous "good" actions to justify subsequent questionable behavior. In politics, this often manifests as leaders believing their righteous goals justify problematic means.

Key aspects:

When political leaders operate from strong moral or religious convictions, they often develop what psychologists call "moral certitude"—an unwavering belief in the righteousness of their position. This certitude creates a psychological framework where actions taken in service of these convictions are automatically justified, regardless of procedural violations or ethical concerns.

Consider a governor who strongly opposes recreational marijuana based on sincere concerns about public health and societal well-being. This conviction may become so central to their identity and perceived responsibility as a leader that they view any tactics to prevent legalization as inherently justified—even if those tactics involve redirecting public funds or circumventing normal fiscal controls.

"The psychological mechanism at work here is not simple hypocrisy but rather a hierarchical moral framework where certain principles (protecting society from drugs) are deemed so important that they override other values (procedural transparency, fiscal propriety) that would normally constrain behavior."

Student 2: But isn't there a difference between having strong convictions and actually breaking rules? The Florida House investigation found that the Hope Florida Foundation hadn't filed required audits and financial disclosures, and some lawmakers said the money trail "looks very much like wire fraud and money laundering." Doesn't that go beyond moral conviction into actual rule-breaking?

You're raising a critical distinction that helps us understand the full complexity of these situations. Yes, there's an important difference between moral conviction and rule violation—and what makes these cases psychologically fascinating is how that difference gets blurred in the mind of the political actor.

Let me introduce another concept that helps explain this dynamic:

Compartmentalization is a psychological defense mechanism where contradictory attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors are kept separated in the mind, preventing cognitive dissonance. In politics, this allows leaders to maintain procedural violations in one mental "compartment" while preserving their self-image as ethical, rule-following individuals in another.

Examples in political contexts:

When faced with evidence of rule violations, political figures often engage in several distinctive cognitive processes:

In the case you mentioned, we see clear examples of redefinition when the administration characterized the funds not as "diverted Medicaid money" but as a "separate charitable contribution" or "sweetener" beyond the state settlement. This linguistic reframing helps resolve the cognitive dissonance between the action taken and the rules governing public funds.

| Leadership Style | Response to Criticism | Psychological Driver | Effect on Accountability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moral Crusader | Dismisses criticism as morally compromised or trivial | Mission protection, moral certainty | Severely undermines institutional checks |

| Pragmatic Operator | Addresses procedural concerns while defending outcomes | Reputation management, outcome focus | Allows limited procedural accountability |

| Identity Leader | Frames criticism as attacks on group/movement | Group solidarity, identity protection | Transforms accountability into loyalty test |

| Technocratic Manager | Engages with process concerns, deflects value judgments | Technical competence validation | Permits procedural but not moral accountability |

The "moral crusader" leadership style—which we often see in leaders with strong religious or ideological convictions—is particularly resistant to criticism because challenges are viewed through a moral rather than procedural lens. When a leader like Governor DeSantis dismisses Representative Andrade's concerns, we're seeing a classic pattern where procedural violations are minimized as irrelevant to the moral mission.

What makes this particularly challenging is that moral mission leaders often genuinely believe their critics are either misguided or malicious. It's not merely a public relations strategy but a deeply held psychological framework that categorizes critics as either failing to understand the importance of the mission or actively working to undermine righteous causes.

However, it's important to note that religious convictions can also function as a source of ethical constraint and accountability. Religious traditions typically emphasize honesty, fairness, and servant leadership alongside moral positions on social issues. The selective application of religious principles to justify certain actions while ignoring religious teachings on procedural ethics reflects motivated reasoning rather than consistent religious application.

Political figures who regularly employ confrontational tactics often develop a reputation for "effectiveness" that further enables problematic behavior. When a leader becomes known for aggressively targeting critics and opponents, this reputation itself becomes a form of insulation from accountability.

The psychology of intimidation operates on multiple levels. Potential critics within government may self-censor rather than risk becoming targets. Media outlets may soften coverage to maintain access. Even opposition lawmakers may calculate that certain battles aren't worth the personal and political cost of engaging.

This environment of intimidation doesn't require explicit threats. A pattern of public attacks on critics, coupled with professional consequences for dissenters, creates powerful incentives for silence that operate through implicit understanding rather than direct coercion.

Strategic ambiguity involves deliberately maintaining unclear boundaries around acceptable behavior to maximize leader discretion while minimizing accountability. By keeping rules vague and enforcement unpredictable, political figures create environments where potential critics must constantly calculate risk, leading to self-censorship.

Key manifestations:

Student 3: I'm struck by how Governor DeSantis described the lawmakers investigating Hope Florida as "stabbing voters in the back." That seems like a particularly aggressive framing that goes beyond just defending his administration. Could you speak to how this kind of rhetoric affects democratic institutions more broadly?

That's an excellent observation that touches on a concerning trend in contemporary political discourse. The phrase "stabbing voters in the back" demonstrates several psychological and rhetorical techniques simultaneously:

This type of rhetoric has significant implications for democratic institutions because it undermines the legitimacy of constitutional checks and balances. When oversight is characterized as betrayal rather than proper institutional function, it becomes more difficult for accountability mechanisms to operate effectively.

Research on political intimidation reveals how confrontational rhetoric creates ripple effects throughout democratic systems:

These effects compound over time, creating governance environments where formal checks remain in place but function with decreasing effectiveness as informal norms of deference develop around powerful executives.

The psychological dynamics that enable questionable political behavior are not simply matters of individual character. They emerge from complex interactions between psychological mechanisms, institutional incentives, social dynamics, and power structures.

Understanding these dynamics is not about excusing improper behavior but about recognizing the systemic nature of political illusions. When we frame political ethics purely in terms of "good people" versus "bad people," we miss the institutional and psychological factors that enable well-intentioned individuals to engage in problematic actions while maintaining positive self-perception.

Effective accountability requires more than moral condemnation. It demands institutional mechanisms that can penetrate psychological defenses, compelling political actors to confront the gap between their self-perception and their actual impact. This requires:

Perhaps most importantly, it requires citizens who understand these dynamics and can recognize when moral certainty, family loyalty, religious conviction, or political effectiveness are being invoked to justify actions that undermine democratic norms and procedures. Only through this awareness can we distinguish between genuine public service and self-serving illusions disguised as righteous leadership.

Student 4: This has been fascinating, but I'm wondering what practical lessons we can take from this analysis. If you were advising an incoming administration on how to avoid these psychological traps, what specific structural safeguards would you recommend they put in place from day one?

That's an excellent forward-looking question that moves us from analysis to practical application. Based on the psychological patterns we've discussed, here are specific structural safeguards I would recommend to any incoming administration:

The key insight from political psychology is that good intentions and personal integrity are not sufficient safeguards against ethical drift. Even the most well-intentioned leaders are vulnerable to the psychological mechanisms we've discussed. Structural safeguards that anticipate these tendencies are essential for maintaining ethical governance.