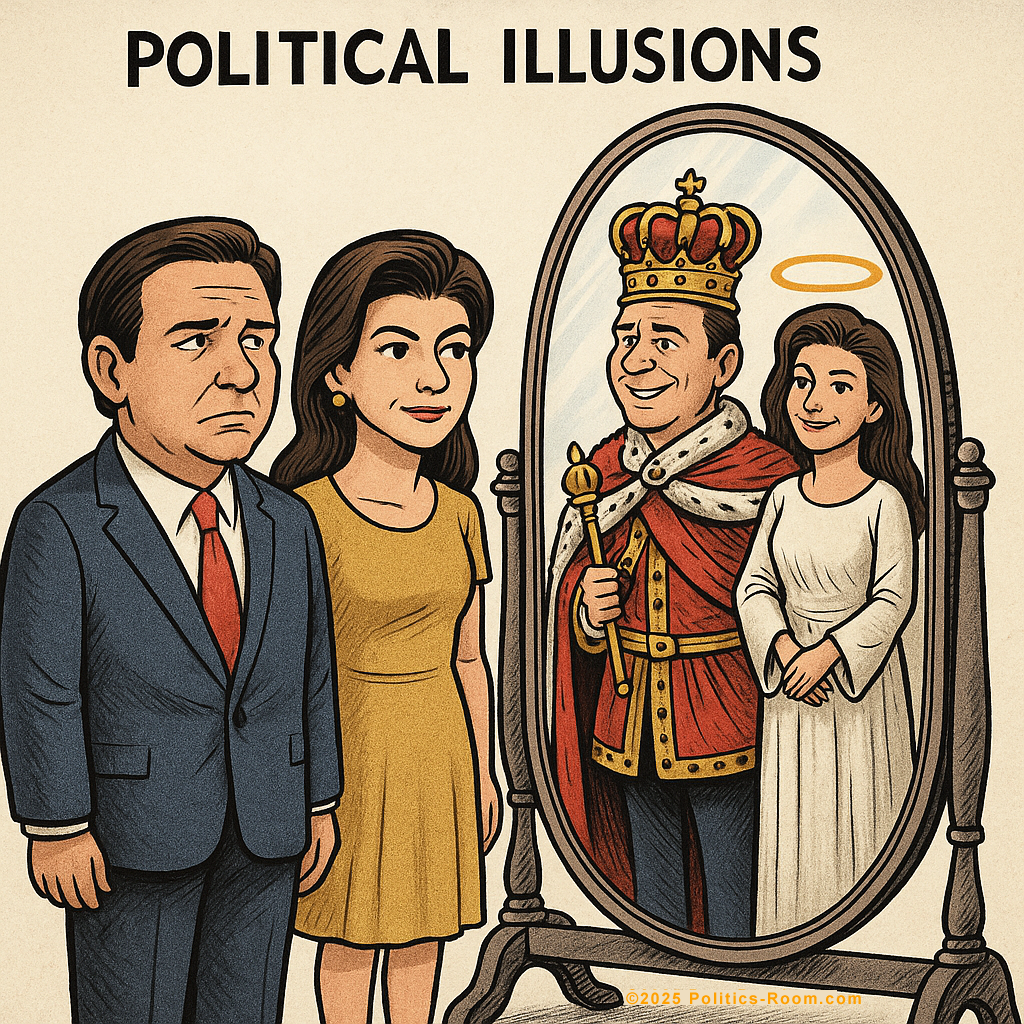

Political Illusions: Psychological Dynamics in Modern Governance

April 25, 2025

This lecture examines the psychological mechanisms that enable political figures to justify ethically questionable actions while maintaining positive self-perception and public support. Using contemporary case studies, we explore how moral conviction, family dynamics, institutional power, and rhetorical strategies create environments where political illusions flourish and accountability diminishes.

Introduction: The Architecture of Political Self-Deception

When political figures engage in ethically ambiguous conduct, they rarely perceive themselves as wrongdoers. Instead, complex psychological mechanisms allow them to maintain a positive self-image while taking actions that outside observers might view as corrupt or improper. This lecture explores the psychological architecture that enables this self-deception and the social dynamics that reinforce it.

Political illusions—the gap between how political actors perceive their own behavior versus how it appears to objective observers—are not simply matters of individual psychology. They emerge from intricate interactions between personal values, institutional incentives, family dynamics, religious convictions, and power structures.

1. Moral Conviction as Justification

Concept: Moral Licensing

Moral licensing occurs when individuals use their positive self-concept or previous "good" actions to justify subsequent questionable behavior. In politics, this often manifests as leaders believing their righteous goals justify problematic means.

When political leaders operate from strong moral or religious convictions, they often develop what psychologists call "moral certitude"—an unwavering belief in the righteousness of their position. This certitude creates a psychological framework where actions taken in service of these convictions are automatically justified, regardless of procedural violations or ethical concerns.

Consider a governor who strongly opposes recreational marijuana based on sincere concerns about public health and societal well-being. This conviction may become so central to their identity and perceived responsibility as a leader that they view any tactics to prevent legalization as inherently justified—even if those tactics involve redirecting public funds or circumventing normal fiscal controls.

The psychological mechanism at work here is not simple hypocrisy but rather a hierarchical moral framework where certain principles (protecting society from drugs) are deemed so important that they override other values (procedural transparency, fiscal propriety) that would normally constrain behavior.

2. Family Dynamics and Political Identity

Political power rarely affects only the individual who holds office. Spouses, children, and extended family often become integrated into a collective political identity. This fusion of family and political identity creates unique psychological dynamics where personal relationships and public service become intertwined.

When a political spouse leads a charitable initiative with close ties to government, the boundary between family projects and official state business can blur significantly. The political figure may genuinely fail to distinguish between advancing their spouse's work and advancing state interests, seeing them as fundamentally aligned.

Concept: Identity Fusion

Identity fusion occurs when personal and social identities become so intertwined that threats to the group (or family) are experienced as personal threats, and vice versa. In political families, this can manifest as an inability to separate personal interests from state interests.

This dynamic becomes particularly powerful when both members of a political couple share ideological convictions and political aspirations. What outside observers might see as nepotism or conflict of interest, the couple perceives as natural extension of their shared mission to serve the public according to their values.

3. Institutional Power and Accountability Erosion

Success in politics often reinforces behaviors that led to that success. A governor who wins reelection by a landslide after taking confrontational positions learns that such approaches work. This creates a reinforcement cycle where accountability mechanisms gradually weaken as political capital grows.

When political figures accumulate significant power within their party or institution, traditional checks and balances may function less effectively. Staff members, appointed officials, and even ostensible oversight bodies may begin to see their role as facilitating the leader's agenda rather than ensuring procedural propriety.

Case Study: The Settlement Redirection Pattern

When government officials redirect settlement funds to preferred causes rather than state general funds, they often justify this through several psychological mechanisms:

- Administrative discretion belief - The conviction that executive officials have legitimate authority to direct funds as they see fit

- Outcome justification - The belief that the positive outcomes of funded initiatives justify procedural shortcuts

- Definitional shifting - Redefining the nature of the funds ("It's not really public money") to avoid cognitive dissonance

These psychological processes allow officials to maintain a positive self-image while taking actions that may technically violate established procedures or norms.

4. Rhetorical Strategies and Cognitive Insulation

Political leaders develop sophisticated rhetorical frameworks that serve both to convince the public and to reinforce their own psychological justifications. These linguistic patterns shape how they—and their supporters—perceive reality.

Attack as Defense

When challenged on ethical grounds, political figures often respond not by addressing the substance of allegations but by questioning the motives of critics. This transforms a discussion about procedural propriety into a narrative about political persecution, shifting the psychological and public focus away from the leader's actions and onto the alleged motivations of opponents.

Terms like "witch hunt," "manufactured controversy," or claiming critics are "threatened" by one's success serve to delegitimize scrutiny rather than engage with its substance. This rhetorical approach helps maintain both public support and the leader's positive self-perception by recasting challenges as evidence of their effectiveness rather than their impropriety.

Definitional Shifts

Another powerful rhetorical strategy involves redefining key terms to avoid cognitive dissonance. When confronted with evidence that settlement funds meant for state coffers were diverted to political causes, a leader might insist these weren't "really" public funds but rather "additional contributions" or "sweeteners." This linguistic redefinition serves to evade established constraints on public fund usage while allowing the leader to maintain their self-perception as law-abiding.

Concept: Motivated Reasoning

Motivated reasoning describes the unconscious tendency to process information in a way that protects one's preferred conclusion. Political figures engage in motivated reasoning when they selectively interpret facts, laws, and precedents to support their preferred narrative about their own actions.

5. True Believers and Echo Chambers

Political leaders rarely operate in isolation. They are typically surrounded by staff, advisors, family members, and supporters who share their ideological commitments and have vested interests in their success. This creates an environment where questionable actions may never face internal challenge.

When a political inner circle consists entirely of ideological allies and personal loyalists, critical perspectives that might identify ethical problems are systematically excluded. What outsiders see as corruption or impropriety, insiders perceive as creative problem-solving or justified assertiveness in service of shared goals.

This dynamic becomes particularly powerful when coupled with the phenomenon of "groupthink"—the tendency for cohesive groups to prioritize consensus over critical evaluation. In such environments, even staff members with initial reservations about an action may convince themselves of its propriety through social influence and the desire to remain loyal to the leader and mission.

6. The Role of Religious and Moral Frameworks

Religious convictions can play a significant role in the psychological justification of political behavior. When leaders view their political role through a religious lens, they may see themselves as defending divine principles rather than merely implementing policy preferences.

This religious framework can create a sense of transcendent purpose that makes procedural concerns seem trivial by comparison. If one believes they are fighting spiritual battles through political means, traditional boundaries between church and state—or between personal morality and public policy—may become blurred.

However, it's important to note that religious faith can also function as a source of ethical constraint and accountability. Religious traditions typically emphasize honesty, fairness, and servant leadership alongside moral positions on social issues. The selective application of religious principles to justify certain actions while ignoring religious teachings on procedural ethics reflects motivated reasoning rather than consistent religious application.

7. Bullying Dynamics and Power Display

Political figures who regularly employ confrontational tactics often develop a reputation for "effectiveness" that further enables problematic behavior. When a leader becomes known for aggressively targeting critics and opponents, this reputation itself becomes a form of insulation from accountability.

The psychology of intimidation operates on multiple levels. Potential critics within government may self-censor rather than risk becoming targets. Media outlets may soften coverage to maintain access. Even opposition lawmakers may calculate that certain battles aren't worth the personal and political cost of engaging.

This environment of intimidation doesn't require explicit threats. A pattern of public attacks on critics, coupled with professional consequences for dissenters, creates powerful incentives for silence that operate through implicit understanding rather than direct coercion.

Concept: Strategic Ambiguity

Strategic ambiguity involves deliberately maintaining unclear boundaries around acceptable behavior to maximize leader discretion while minimizing accountability. By keeping rules vague and enforcement unpredictable, political figures create environments where potential critics must constantly calculate risk, leading to self-censorship.

Conclusion: Beyond Individual Psychology

The psychological dynamics that enable questionable political behavior are not simply matters of individual character. They emerge from complex interactions between psychological mechanisms, institutional incentives, social dynamics, and power structures.

Understanding these dynamics is not about excusing improper behavior but about recognizing the systemic nature of political illusions. When we frame political ethics purely in terms of "good people" versus "bad people," we miss the institutional and psychological factors that enable well-intentioned individuals to engage in problematic actions while maintaining positive self-perception.

Effective accountability requires more than moral condemnation. It demands institutional mechanisms that can penetrate psychological defenses, compelling political actors to confront the gap between their self-perception and their actual impact. This requires robust checks and balances, truly independent oversight, protection for whistleblowers, and media environments that can sustain critical coverage despite potential retaliation.

Most importantly, it requires citizens who understand these dynamics and can recognize when moral certainty, family loyalty, religious conviction, or political effectiveness are being invoked to justify actions that undermine democratic norms and procedures. Only through this awareness can we distinguish between genuine public service and self-serving illusions disguised as righteous leadership.

References and Further Reading

- Haidt, J. (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon Books.

- Tavris, C., & Aronson, E. (2015). Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me): Why We Justify Foolish Beliefs, Bad Decisions, and Hurtful Acts. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Swann, W. B., Jr., & Buhrmester, M. D. (2015). Identity Fusion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), 52–57.

- Kunda, Z. (1990). The Case for Motivated Reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498.

- Janis, I. L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Houghton Mifflin.

- Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979). Biased Assimilation and Attitude Polarization: The Effects of Prior Theories on Subsequently Considered Evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37(11), 2098–2109.

- Merritt, A. C., Effron, D. A., & Monin, B. (2010). Moral Self-Licensing: When Being Good Frees Us to Be Bad. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(5), 344–357.