April, 2025

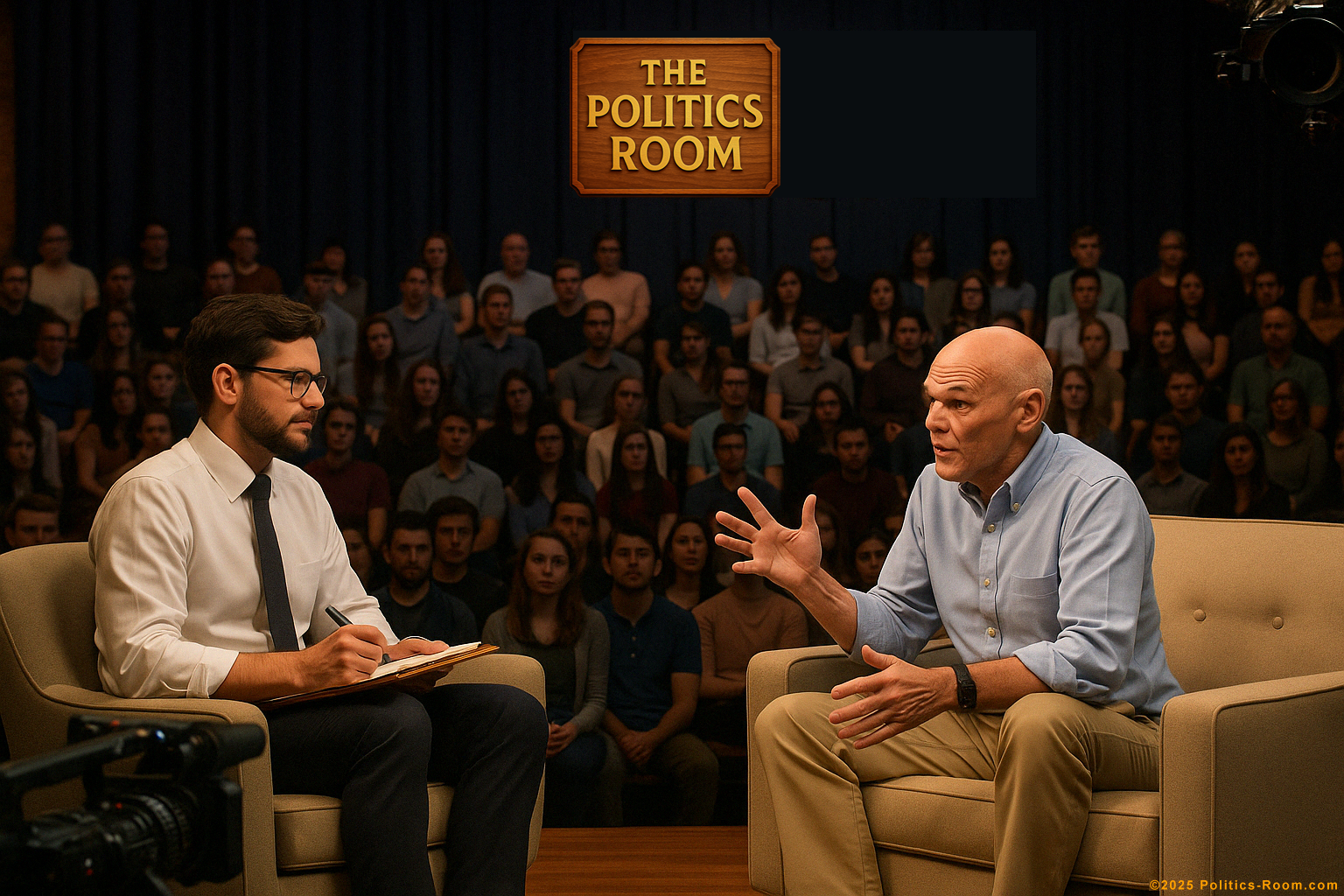

The University Auditorium is packed with students, faculty, and community members for this special live edition of "The Couch Room." The stage features a comfortable blue couch and matching armchair arranged at an angle, with warm lighting creating an intimate atmosphere despite the large venue. Dr. Marcus Bennett sits in the armchair with a notepad, while James Carville, dressed in his signature style—crisp button-down shirt with rolled-up sleeves—settles into the couch. The audience buzzes with anticipation as the cameras begin rolling.

Dr. Bennett: "Good evening and welcome to this special live edition of The Couch Room. I'm Dr. Marcus Bennett, and tonight we're exploring the psychology of political identity and party dynamics with one of the most incisive and provocative political strategists of our time. James Carville has been called the 'Ragin' Cajun,' the architect of Bill Clinton's 1992 victory, and more recently, the conscience—or perhaps the gadfly—of the Democratic Party. James, thank you for joining us tonight."

Carville: "Thank you, Dr. Bennett. It's good to be here with you and this great audience. I'm looking forward to a real conversation about where we are and where we're going."

Dr. Bennett: "James, you've recently made some provocative statements suggesting that the Democratic Party might be better served by a 'schism'—with progressive elements potentially forming their own party. This is a dramatic departure from the traditional 'big tent' approach. What led you to this conclusion?"

Carville: "I've long believed that being a Democrat means you're part of a coalition, and in a coalition, partners have to go out of their way to try to incorporate and get along with other people. That's how we build a successful governing party."

Carville: "But after the 2024 election—a truly less than satisfying experience—I was hoping Democrats would learn that we need more relevant, more direct arguments to make to the American people. Instead, I saw organizations like American Voices holding conferences where they had bowls of buttons with different pronouns for people to wear. After we just got shellacked in an election where identity politics was a major vulnerability!"

Identity hierarchy theory examines how individuals and groups prioritize different aspects of their self-concept. This hierarchical structuring determines which identities become most salient in decision-making and value formation:

Political conflicts often arise when groups prioritize different levels of this hierarchy, creating fundamental disagreements about which identities should guide policy decisions and resource allocation.

Dr. Bennett: "You're describing what psychologists would call competing identity hierarchies—fundamental differences in how people organize their sense of self in relation to society. In your view, has this difference become so pronounced that it's created an unbridgeable gap within the Democratic coalition?"

scene-description - Close-up of Carville gesturing emphatically as he explains his position.

Carville: "I think it might have. Look, there are two fundamentally different worldviews here. There are people who believe they are the wave of the future, that people like me are old, antiquated, stuck somewhere in the past. They believe there are tens of millions of 'sleeper' people out in the country just waiting for the true progressive argument to be activated at the sound of the trumpet of real left-wing identity politics."

Carville: "Meanwhile, we've got places like San Francisco and New York where progressive governance has driven cities into the ditch, and voters are electing more pragmatic leaders to clean up the mess. The evidence just doesn't support their theory."

Dr. Bennett: "That raises an interesting question about the psychology of political movements. Let's pause and take a question from the audience."

Student: "Mr. Carville, don't all political movements need an idealistic wing that pushes boundaries? Isn't there a risk in ejecting the progressive energy from the party?"

Carville: "Great question. Yes, parties need vision and energy. But there's a difference between pushing for bold policies and being detached from electoral reality. I want universal healthcare too. I want action on climate change. I want greater economic equality. On 85% of the substance, I actually agree with the progressive wing."

Carville: "The problem is when that energy gets channeled into attacking other Democrats rather than defeating Republicans. Look at David Hogg, the vice chairman of the DNC. He's talking about raising $20 million to primary other Democrats! When you're a vice chairman of the Democratic National Committee, you have a fiduciary duty to the organization. Your job is to help beat Republicans, not other Democrats."

Political psychology identifies distinct patterns in how groups direct their competitive energy:

These dynamics can create situations where members of a political coalition may view their intraparty rivals as more threatening than their interparty opponents.

Dr. Bennett: "What you're describing reflects a classic psychological phenomenon in group dynamics—when ingroup/outgroup boundaries shift, and members begin to view certain factions within their own group as the primary threat rather than external opposition. How do you think this has evolved in the Democratic Party?"

scene-description - Dr. Bennett explaining a psychological concept as Carville listens attentively.

Carville: "That's exactly it. Look at AOC and the Squad. With the exception of AOC's first primary, they never run against Republicans! They only run in deep blue districts where the real contest is the Democratic primary. Their entire focus is on internal competition, not actually defeating the opposition party."

Carville: "And then you've got Bernie Sanders, who has run for president twice as a Democrat, lost both times, and then goes back to being an independent. He never built the Democratic Party. He used its infrastructure when convenient, but his loyalty was always to his own movement, not the party."

Carville: "When you beat a Republican, I'll be impressed. But if your entire political identity is built around attacking other Democrats, you're not helping. You're hurting."

Dr. Bennett: "Let's dig deeper into this idea of party identity. Political psychologists often talk about how parties function as both strategic vehicles and psychological homes. Are you suggesting that these progressive elements don't actually want the Democratic Party as their home—they just want its resources?"

Carville: "That's a really insightful way to put it. Yes, I think many of them are using the Democratic Party as a vehicle without sharing its fundamental values or priorities. And my question is: why are you so anxious to have the word 'Democrat' in the description of what you do if you spend all your time attacking Democrats?"

Carville: "I'm not suggesting everyone who considers themselves progressive should leave. But if you think pronouns are more important than economic policy, if you think attacking other Democrats is more important than defeating Republicans, if you think America is fundamentally flawed beyond redemption—maybe you should form your own party. Call it the Socialist Party, the Justice Party, the Progressive Party—whatever you want. Just don't call it Democratic."

Successful political coalitions balance several psychological needs that can become sources of tension:

When these balancing factors break down, coalitions may fragment as subgroups determine that the psychological and strategic costs of participation outweigh the benefits.

scene-description - Wide shot showing audience reaction as Carville makes a provocative point.

Dr. Bennett: "Let's talk about the pathway forward. You've mentioned a parliamentary model where different parties negotiate coalitions after elections. How do you envision this working in the American two-party system?"

Carville: "Well, look, it's imperfect given our system. But there's nothing against having distinctive parties that form coalitions after the election. Maybe you come up with your own name and platform. Then after the election, we sit down and say, 'Okay, we want to be part of a governing majority, and we have these things that we want you to do to bring us in.' That's how parliamentary systems work."

Carville: "This might actually lead to more honest politics. Right now, we're pretending to be one big happy family when we're not. We have fundamentally different views about what's important and how to win elections."

Dr. Bennett: "Let's take another question from the audience."

Professor: "Mr. Carville, isn't what you're proposing essentially guaranteeing Republican victories by splitting the Democratic vote? How is this not just a recipe for minority rule?"

Carville: "That's the million-dollar question, isn't it? I don't have a perfect answer. But I'll say this: the current arrangement isn't working either. We've lost the presidency, the Senate, and the House. The progressive wing claims this happened because we weren't progressive enough, while the evidence suggests exactly the opposite—that identity politics and progressive rhetoric are costing us in swing districts and states."

Carville: "Maybe we need to hit rock bottom before we can rebuild. Maybe we need to clarify what the Democratic Party stands for, even if that means some people leave. And maybe in time, we develop a culture where different parties can form governing coalitions without destroying each other."

Dr. Bennett: "You've been particularly vocal about the damage done by identity politics. From a psychological perspective, why do you think this approach alienates so many voters?"

scene-description - Split screen showing Carville explaining his concerns about identity politics with audience reactions.

Carville: "Because most people don't think about themselves primarily in terms of immutable characteristics. They think about themselves as individuals with agency, as citizens, as workers, as family members. When politics becomes all about putting people in identity boxes, it feels reductive and alien to how most people experience their lives."

Carville: "And there's something profoundly undemocratic about it. The whole idea of democracy is that we're equal as citizens, regardless of our backgrounds or characteristics. Identity politics turns that on its head and says what matters most is your group identity, not your individual citizenship."

When individuals perceive threats to their behavioral freedoms or self-conception, they experience psychological reactance—a motivational state aimed at restoring those threatened freedoms:

In political contexts, policies or rhetoric that appear to threaten established identities or impose new social norms often trigger reactance, particularly among individuals who place high value on tradition and personal autonomy.

Dr. Bennett: "What you're describing connects to a concept called psychological reactance—when people feel their autonomy or self-definition is threatened, they often respond by moving in the opposite direction. Do you think Democratic messaging on identity issues has triggered this reactance among voters?"

Carville: "Absolutely. When you tell people they need to change their language, adopt new terminologies, or that they're somehow complicit in systems of oppression just by existing, you create exactly that reactance. People don't like being told they're bad people because they use the wrong words or haven't fully internalized the latest academic theories."

Carville: "And the tragedy is, this alienates potential allies. I want a more just, equal society too. But the tactics and rhetoric of the identity left are counterproductive to achieving those goals. They push away the very voters we need to build majorities."

Dr. Bennett: "Let's talk about the practical way forward. If you were advising Democratic leadership today, what concrete steps would you recommend to reset the party's image and approach?"

scene-description - Carville leaning forward and counting on his fingers as he outlines his recommendations.

Carville: "First, make economic issues central. Trump is giving us a gift with his chaotic trade policies and tariffs. They're hurting American families, creating market instability, and raising prices. Democrats should be talking about this non-stop—how we'll deliver concrete economic benefits to working families."

Carville: "Second, stake out clear positions on issues where the majority of Americans agree with us. Abortion rights, protecting Social Security and Medicare, reasonable gun safety measures—these are winning issues where Republicans are out of step with public opinion."

Carville: "Third, enforce party discipline. If you're in Democratic leadership, your job is to help elect Democrats, not attack them. The DNC chairman needs to bring David Hogg into line or ask for his resignation. You can't have the vice chairman of the party raising money to primary sitting Democrats."

Carville: "Fourth, reconnect with rural and working-class voters. Show up in places Democrats have written off. Talk about agricultural policy, infrastructure, healthcare access in rural areas. Make clear that the Democratic Party isn't just for urban professionals."

Carville: "And finally, yes, maybe it's time for some honest conversations about whether all the current factions really belong in the same party. It's been a long tradition that the Democratic Party is a coalition, but coalitions can change over time."

Dr. Bennett: "You're describing what political scientists would call a realignment period—when longstanding coalitions break down and reconfigure. These are often turbulent times in a democracy. Do you see parallels to other realignment periods in American history?"

Carville: "Absolutely. Think about the 1960s and 70s when the Democrats lost the Solid South after embracing civil rights, or the realignment of white working-class voters toward Republicans that accelerated under Reagan. These were painful transitions, but they created clearer choices for voters and ultimately more coherent parties."

Carville: "What we have now is a Democratic Party trying to be all things to all people and ending up being nothing clear to anyone. We're trying to simultaneously be the party of Goldman Sachs and Occupy Wall Street, the party of suburban professionals and urban activists, the party of Silicon Valley and labor unions. At some point, these contradictions become untenable."

Dr. Bennett: "Let's take one more question from the audience before we wrap up."

scene-description - Audience member asking a question with Carville listening attentively.

Community Member: "Mr. Carville, you've been critical of the progressive wing, but what about corporate Democrats who seem more interested in donor money than bold policies? Aren't they also part of the problem?"

Carville: "Fair question. Look, I'm not saying the Democratic establishment is perfect—far from it. There are plenty of Democrats who are too cozy with donors, too cautious on economic policy, too willing to compromise core values. That's a legitimate critique."

Carville: "But here's the key difference: those Democrats generally win elections. They help build and maintain Democratic majorities that can actually govern. They understand that you have to win power before you can use it."

Carville: "The progressive critique of the Democratic establishment would be a lot more compelling if progressives were consistently winning in competitive districts and states. But they're not. They're winning in deep blue areas where any Democrat would win, and they're often losing in places where more moderate Democrats might have a chance."

Carville: "I'm results-oriented. I want policies that help working families, expand healthcare access, address climate change, protect civil rights. But you don't get those policies without winning elections. And if your approach consistently loses elections, I don't care how pure your intentions are—you're not helping achieve those goals."

Dr. Bennett: "As we come to the close of our conversation, I'm struck by how much your analysis reflects fundamental psychological tensions in political organization—the balance between purity and pragmatism, between expressing values and achieving results, between individual identity and collective action."

Dr. Bennett: "You've been described as a prophet within the Democratic Party—often warning of dangers that others ignore until it's too late. What final message would you like to leave with our audience tonight?"

scene-description - Final wide shot of Carville delivering his closing thoughts with Dr. Bennett listening."

Carville: "I'd say this: Democracy itself is under threat right now. We've got a president ignoring court orders, threatening universities, using the government to punish his enemies. The stakes couldn't be higher."

Carville: "Given those stakes, we need a Democratic Party that's focused on winning—winning elections, winning arguments, winning the battle of ideas. That means being strategic, being disciplined, and yes, sometimes being uncomfortable with certain alliances or compromises."

Dr. Bennett: "Let's address something you've been vocal about recently. You've suggested that progressives like those we had on our stage earlier should form their own party rather than remain within the Democratic coalition. Can you elaborate on that view?"

Carville: "Look, I've seen this play out multiple times now. 2016, 2020—how many times do Democratic voters have to tell you we don't want you? Give Bernie Sanders credit, he raises a lot of money, he's got a very passionate following. And he wins in Vermont. But that's about it."

Dr. Bennett: "But many of the policies supported by progressives—Medicare for All, climate action, higher minimum wage—actually poll quite well with the broader public."

Carville: "The question is simple: do we want a more ideologically pure, committed party or do we want to win elections? It's really that simple. These progressive candidates have run in primary after primary, they were all really well-funded. Biden didn't even show up on the ballots until South Carolina, so it's not like they didn't have a shot to make their case. They made their case, and people kept rejecting it. What part of this don't they understand?"

Dr. Bennett: "From a psychological perspective, there's an interesting tension here between ideological consistency and coalition-building. You seem to be arguing that too much ideological purity becomes self-defeating."

Carville: "Exactly. The Democratic Party is a coalition. Coalitions have a more difficult time messaging because there are many members in the coalition. Maybe if we do as I suggest and let these leftists form their own party, we'd have a chance to put out a more unifying message."

Dr. Bennett: "What kind of message do you think would resonate more effectively?"

Carville: "I think we should run more to the economic lift, if you will—higher minimum wage, more taxes on rich people, that kind of stuff. I think there are some elements of good messaging there that we can take advantage of going forward."

Dr. Bennett: "What about the argument that progressives are actually expanding the Overton window, making previously 'radical' ideas more mainstream and creating space for moderate Democrats to advocate for policies they couldn't before?"

Carville: "That's a fancy way of saying they're losing. Look at what's happening right now with Trump's tariffs. While progressives are debating abstract theory, American consumers are getting hammered. Congress could pass a bill tomorrow to reclaim their tariff authority, but this group of Republicans up there are so acquiescent to whatever Trump says."

Carville: "Democrats should be saying 'If you give us one-third of the Republicans, we can overturn this policy in an afternoon and end this madness.' I don't know why they aren't making this simple, relevant, doable message. Let's stop the bleeding, let's stop it now. We can do it! That speech writes itself."

Dr. Bennett: "You've suggested rebranding tariffs as the 'Trump Sales Tax.' Is that the kind of messaging shift you're advocating?"

Carville: "Yes, we could do a better job of communicating that it's the consumer who pays for this. I think it's breaking through—these things are not very popular, people don't much like them. But we need to hammer it home."

Dr. Bennett: "Let me ask you about the criticism that you're too dismissive of the progressive wing. Some would argue they represent the future of the party, especially among younger voters."

Carville: "I understand the desire for moral purity in politics. I understand wanting your party to perfectly reflect your values. But politics is ultimately about power—who has it and what they do with it. And right now, we're losing. We're losing because we're divided, because we're focusing on the wrong issues, and because we're more interested in internal battles than external victories."

Carville: "So whether it's through a realignment, a schism, or just a good old-fashioned wake-up call, something needs to change. The Democratic Party needs to decide what it stands for, who it represents, and how it's going to win. Because if we don't, the consequences for this country will be devastating."

Dr. Bennett: "James Carville, thank you for this candid and thought-provoking conversation. You've given us all a great deal to consider about the future of Democratic politics and the psychological dynamics that shape our political landscape."

Carville: "Thank you, Dr. Bennett, and thanks to this wonderful audience for their attention and excellent questions."

As the audience rises for a standing ovation, the cameras capture the diversity of reactions—some nodding vigorously in agreement, others with thoughtful or concerned expressions, and a few visibly disagreeing but engaged nonetheless. Dr. Bennett and Carville shake hands as the lights begin to dim, concluding an evening that has surely given everyone in attendance much to discuss on their way home.